Through David’s tragicomic one-man show Pieces of a Man he attempts to “re-author” a traumatic past with creativity and joy.

“Many years later the boy was no longer sure what was true or imagined. He could only feel pain, anger and sadness.”

So writes Jack Santcross, who survived the Nazi concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen as a child. His words brought home to me how my father — another child survivor – must have struggled even to identify the trauma driving him uncontrollably to a tragic end.

As I approached my 40th birthday in 2019, I had my latest mid-life crisis. Emotionally paralysed, I saw my late father hanging over me. Musci Marcello Labi had a Jewish family, a big house and a successful business, by my age… I was failing to live up to his values. On the other hand, he later declined into financial disaster, depression, ill-health, and death. But that made me feel even worse. Was I doomed to suffer the same fate?

In addition, there were many unanswered questions about a life that had featured globe-trotting, casinos, secret agents, Russian gangsters — even an unexplained bomb in a sleepy suburb of northwest London. I had to explore his story before it was too late. In Israel, I interviewed his sister — my aunt, whom I hadn’t seen for 16 years. In London, Toronto, and Rome, I harrassed other family and friends.

A project that began as a podcast became a book, then a film, and finally a one-man stage show called Pieces of Man. I wrestled to confront my father’s story — and my own.

A Libyan-Italian Jew born in 1938, Musci Marcello Labi lost his father and was taken with his mother and sister across seas and up mountains. Captive, he saw snow for the first time. And he survived the stupefying horror of Bergen-Belsen. Just one small human amid millions targeted by the Nazis’ exterminating drive.

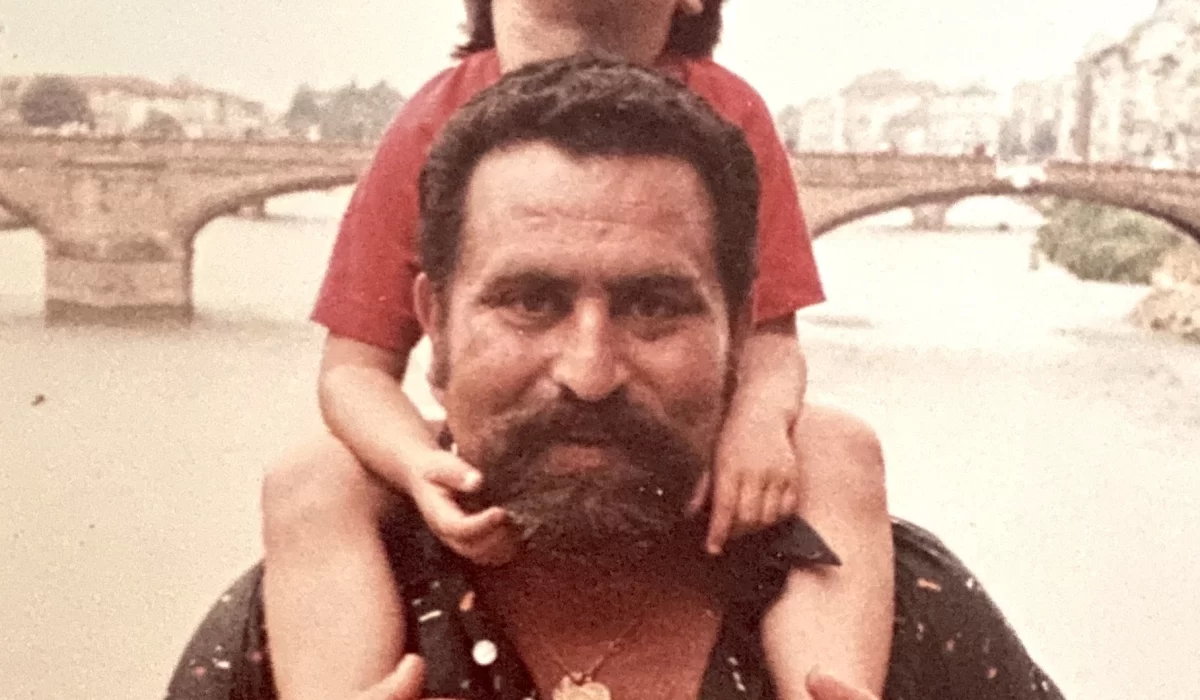

Post-war in 1950, he moved to Israel where he constructed a powerful alpha-male personality to conceal the terrified boy who must have remained inside. He moved to London in 1965 when he met and married my mother. Marcello was so forceful, so funny, so temperamental, so present — that it was hard for me to understand how much his every move must have been governed by that pain, anger and sadness.

As I grew up in London, my father seemed from another world. He had different ways of speaking and thinking — and my education drove me further away. I defined myself in opposition to him, and avoided him when he most needed support. When he died in 2003 — I was 22 — I acquired a burden of guilt to carry far beyond his death.

Creating and performing his story has helped me deal in some way with this complex legacy. To make him live on —not just his difficult aspects, but his creativity, his brilliance, his warmth. And to deal in some way with the trauma he was unable to confront himself. It’s important for us — all of us — to break the cycle of pain, anger, and sadness. The cycle of trauma. You don’t have to be the child of a Holocaust survivor to face a heavy legacy. But you do have to look into the darkness — so you can find the light.

Originally published by the Jewish Chronicle, Sep 2022